- WICKNELL CHIVAYO left school at 15

- DISGRUNTLED Zimbabwe police stage uniform protest.

- MNANGAGWA wife Auxillia drops charges against nine women who boed her in Manicaland

- O.J. Simpson dies of cancer , aged 76.

- South Africa ANC is the cause of ZIMBABWE troubles claims Zimbabwe opposition politician Job Sikhala

Zimbabwe’s Lack Of Political Will To Enforce Judicial Rulings Risks Collapsing Into Somalia Failed State Situation

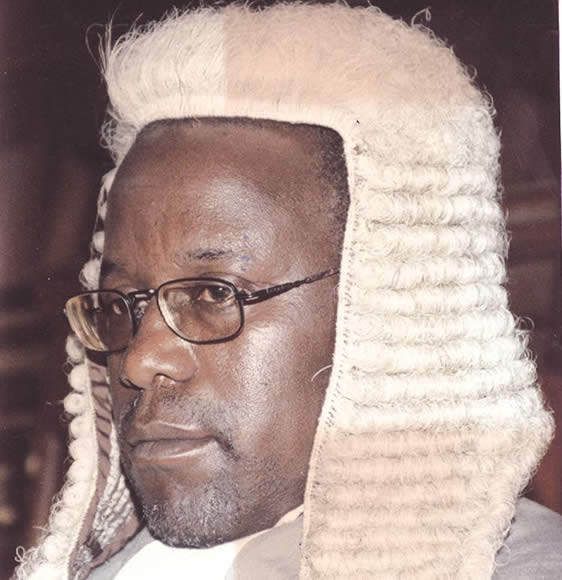

FORMER High Court of Zimbabwe judge, Justice Moses Chinhengo, says the absence of political will to enforce judicial rulings and the law in general is a threat to the rule of law in the country, which could lead to an unfortunate situation where the country operates under either the rule of man or the rule by law.

Such a development could result in the country degenerating into a failed state like Somalia.

Chinhengo made the remarks in Harare a fortnight when he gave a public lecture on the Rule of Law organised by a local legal research think-tank, the Centre for Applied Legal Research, in conjunction with the Embassy of Netherlands in Zimbabwe.

Chinhengo said he was seriously worried by the increasing cases in which members of the Executive, public officials and the State itself were wantonly disregarding court orders, provisions of the Constitution and international treaties among others things that they feel uncomfortable with, a development that seriously undermines the rule law.

Chinhengo’s remarks come at a time when the Constitutional Court (ConCourt) has just convicted the country’s Prosecutor General, Johannes Tomana, for wilful disregard of several court orders, while Local Government, Public Works and National Housing Minister Saviour Kasukuwere, has defied a High Court ruling ordering him to re-instate Gweru Mayor, Hamutendi Kombayi, and the city’s councillors that the court ruled were unprocedurally dismissed.

The police has also repeatedly ignored court orders, while government has been reluctant to fully implement the new Constitution and some provisions of international statutes, which it is party to.

“There is no political will to implement (the laws). This is one of the points I have always said about Zimbabwe. Whether we are going to the United Nations to sign the laws… why do we sign if we do not want to implement? We should be a nation enough to say: ‘In our customary law, we cannot do it (so) we are not prepared to sign’. Once we have signed, we must sign consciously and implement what we sign.

“Here we have a Constitution, which three major political parties agreed upon (which says) we will have devolution, (but) no one is doing anything about it. We will have independent town and city councils, which cannot be fired at the whim of the Minister of Local Government, (but) it still happens that they can be fired, so the point I am saying is that as Zimbabweans we need to be mature and do what we agree on. We must implement our Constitution,” said Chinhengo, who was one of the three drafters of the country’s new supreme law that came into effect two years ago.

Efforts to re-align the old laws of the country with the new Constitution have been done selectively and the process is moving at a snail’s pace with government always reverting to using the laws that were replaced by the new Constitution amid complaints by the opposition that the ruling ZANU-PF party is reluctant to implement the new supreme law in the letter and spirit.

One glaring example is President Robert Mugabe’s appointment of 10 ministers for provincial affairs to posts that are not provided for in the current Constitution, based on the system of provincial governors that was discarded together with the Lancaster House Constitution.

The current Constitution, which provides for devolution of power, says there should be provincial councils formed on the basis of the popular will of the people as expressed in the results of a previous election.

Chinhengo said it was amazing that in each and every situation, Zimbabweans always come up with novel — but unacceptable — explanations to avoid implementing the law.

“Everyone agrees that the Constitution is the supreme law, then you have an Act of Parliament, which is not consistent with the Constitution. The police will tell you that they are implementing the Act, and I think in one or two cases even the judges have said that they are implementing the law as it exists in the Act, even though they are aware that the supreme law is like this.

“Politicians perhaps believe that the rule of law is a threat in some respects or that the rule of law, if it becomes pervasive, might mean weak governments, but I can tell you that where you don’t have the rule of law, the result is not just authoritarianism in some respects, but more devastatingly weak in operating governments like we have in Somalia and all these places where there is no rule of law. If we do not maintain the rule of law, it is not unimaginable that we can sink to those levels. Rule of law ensures that we could have stronger governments, stronger institutions.

“Another threat to the rule of law is refusal to obey (court) orders. The courts are critical to the maintenance of the rule of law, but of course they do not have the power to enforce their decisions.”

Chinhengo also added that Tomana’s arguments in his failed ConCourt application, in which he sought to get what he claimed to be his Constitutional right to protection against interference by anyone, was another classic example of the novel tricks employed by public officers to avoid complying with the law.

“The rule of law simply means (that) when the court of law makes a decision, of course that decision has to be obeyed and particularly when the Supreme Court makes a decision, it must be obeyed. I have been a judge, here and in Botswana… even two people leaving a courtroom don’t agree with a judge’s decision, but the order of things is that you must accept that order. We cannot have a situation where the Supreme Court of Zimbabwe – duly constituted – rules on a matter and one says I don’t agree with the decision. That disagreement doesn’t matter. We all disagree with so many things that have to be done and in cases of court decisions, no one of us has an option to disobey that order. I hope we do not return to the situation where each time the Executive did not agree with a court decision, they amend the law.

“The things that impact on the rule of law are so many… longevity in office, patronage and things like that… its not just about Zimbabwe, I must say.”

An independent minded judge known in the judicial circles for his radical views on constitutionalism, Chinhengo is among some of the country’s highly regarded judges who left the Zimbabwean bench and ended up sitting on foreign benches.

When the Financial Gazette sought to elicit from the former judge the circumstances under which he ended up deciding to leave the bench, Chinhengo, who claimed to be enjoying his freedom to the hilt, could only said: “There were a number of issues that led me to make that decision.” He, however, could not divulge the issues.

After being a judge of the High Court of Botswana for eight years, Chinhengo resigned when he was invited to come and become one of the drafters of the country’s Constitution. A commissioner with the International Commission of Jurists, he is now practicing law as an arbitrator and a mediator.